Last September, on my yoga mat in my backyard, I gazed onto the lawn and felt, from somewhere in the back of my head, a tug. Something pulling my attention into the grass. It echoed the visual warp common to psychedelics — I felt, suddenly, like I’d taken on mushrooms — and so I gave into it. The grass subsumed my vision. My center moved out of my head and onto the same plane as the lawn. I looked into the grass, but also out of it. This lasted just a few seconds, but when my perspective returned back between my eyes, I felt that I’d gone through a looking glass. I gazed up at the trees to re-center, saw a dance in their leaves, and then I realized:

Everything was fine. Everything had always been fine. Everything would always be fine.

It wasn’t a thought. I knew it. And I still know it. In the months leading up to that moment, I’d been writing on development of the mystical experience scales used in psilocybin trials. I’d gotten curious about them because while my own psychedelic use had been profound, strange, beautiful, and useful, it had never been — psychometrically speaking — “mystical.”1

It was fun. I got to do personal integration while I wrote a piece. And I learned some stuff — about science but also myself. Several people I talked to seemed to want to nudge me into opening towards mystical experience. Bill Richards, the head guide for the early psilocybin trials at Hopkins, corrected me multiple times when I explained that I hadn’t had one — “yet.”

And so, I thought, sitting there in the grass feeling the deepest equanimity I’d ever experienced, here it was.

Now I’m less sure. I think what I experienced was equally interpretable as something like a jhana.2

—

My understanding of the jhanas prior to the retreat had come mostly from reading Twitter out of the corner of my eye. I followed Nick, I’d read Scott’s posts, and I’d done some light googling. But I was not a meditator. In retrospect, I was actually pretty ignorant about meditation. (I took an 8-week Compassion Cultivation Training course back in 2015 and had sat ~20 hours but did not develop a practice.) Jhanas were intriguing, but I was also a bit skeptical, and since I was not equipped to investigate that skepticism, I didn’t pay close attention.

Then in January, Nadia pitched what would become her Asterisk piece. Her initial idea had been to focus on the jhana scene: who are these people allegedly finding bliss in their bedrooms, what are they, actually doing and where do they fit into San Francisco’s long history as a playground of hedonistic self-experimentation? That changed after Nadia went on a Jhourney retreat and her piece evolved from social scienceish to a personal narrative of her (at times profound) experience. Which convinced me to sign up too.

I’m now about a month back. I gave it some time to settle. While this was very true on the first day back, it remains true today: I feel — I say this carefully, and somewhat hesitantly — changed.

Which I didn’t totally expect. I realize now that I went into the retreat with a lot of gaps: on what the jhanas are, how they fit into the broader meditation landscape, and what you’re supposed to do with them. I want to fill in some of those gaps.

The first gap is how you enter jhana. Most of what I’d read about this was from experienced meditators, save Nadia, and she was basically gifted them, so that didn’t help. (While I started drafting this piece, Nadia wrote a guide, which is very useful. I won’t replicate it, just add my personal experience.) The process is important. It might be more important than the jhanas.

The second is that the common shorthand of jhanas=bliss is good marketing, but it’s a synecdoche that’s unrepresentative of the spectrum of experience. I think its usefulness is going to end soon as more people learn, practice, and write about these states.

And the last gap is what you’re supposed to do with the jhanas once you find them.

You should read this as a novice’s retreat report. I’m a meditation baby. There are lots of things I don’t understand, context I absolutely don’t have, likely things I’ve gotten wrong, and I have soo many questions. But I did figure out how to access jhana in two days. And hopefully my freshness will be useful.

Getting in

Here’s the mental model I started with:

Step 1: Become extraordinarily concentrated on a single point, like a monk, like Buddha

Step 2: ?????

Step 3: Bliss on demand

I did enough research while editing Nadia’s piece to dispel some but not all of that. In particular, what her piece didn’t answer for me — what nothing I read really did — is what steps you need to take to do step one, and what actually happens in step two.

This is a feature more than a bug. Jhourney’s line, borrowing from Romeo Stevens, is that until you’ve entered a jhana, the instructions to do so read like poetry. After, they read like an instruction manual. But a lot of subjective experience is in fact like this. You don’t learn how to ride a bike by reading about it.

Here is how Leigh Brasington, author of Right Concentration, describes the process:

“The move from access concentration [a state where you are fully with your object of meditation and background noise, if it’s there, is wispy at its strongest] is to shift your attention to a pleasant sensation and stay with that as your object of attention, ignoring any background thinking. If you can stay with your undistracted attention on the pleasant sensation, then pīti [glee, rapture, the main characteristic of the first jhana] will arise.”

Brasington teaches jhanas through focus on the breath. After you’ve built up strong enough concentration, you switch your attention to a “pleasant sensation” and center on that until it subsumes your entire focus. There’s only a handful of popular books on jhana,3 but the majority teach it this way.

Jhourney teaches this differently. They skip the shift to the pleasant sensation and start with it — through a combination of relaxation and mettā,4 or lovingkindness meditation (as Nadia’s description suggests, any positive or pleasant emotion will work here). Their core instructions boil down to:

Cultivate enjoyment/mettā

Cultivate relaxation

Observe the process

There is more verbal instruction, there’s details in the practice book, and there’s plenty of time for Q&A + a few practice interviews, but by and large, that’s it. This is the trick. This is the discovery that pre-dates Buddha, the secret locked behind monastery walls, the alchemical feat attainable by one monk in a million, what everyone on your feed is doing before they seem to be tapping into ecstatic pleasure. You get to jhana by relaxing, finding pleasure, paying close attention to that process, and allowing it to amplify as you do.5

Here’s how I got to the point where that makes sense.

I’d tried metta during the course I took in grad school, and it didn’t click for me. It felt false to (as I thought of it) “conjure” feelings. When Jhourney introduced this as the week’s practice, I felt a similar feeling as when I’m asked by some effervescent facilitator I just met to do a group icebreaker.

I resolved to try, with the assumption that I could change course if things weren’t working. Jhourney encourages experimentation and fast failure.

I didn’t really enjoy my first day. I spent a lot of it on the lawn. It was nice in the way that lying in the sun and not working is usually nice. I found that after some initial resistance to starting metta, it did feel, yea, okay, pleasant to think happy thoughts about people. But I struggled to sit for more than 45 minutes, and I still didn’t understand how any of this got to jhana. My reflection from that day describes feeling unfocused, confused, and discouraged.

I realized, in fast succession, two things I was doing wrong. The first was not relaxing deeply enough. We did a relaxation meditation on the second morning. This, I realized, rhymed with yin yoga practice. In yin, you hold each pose for several minutes. With enough attention on where you hold tension, there always a way to release a little more. Every second of the pose feels like a different pose. The meditation equivalent of that is almost exactly the same. I scanned my body for tension, I relaxed it.

The second thing I realized was that I was creating too much internal mental tension in the process. (Weirdly, the CCT class I took never covered this. I wish they had, because I might have enjoyed myself more.) There’s a subtle difference between recognizing and pushing aside a distracting thought, and acknowledging and releasing a distracting thought. One leads to tension and tightening -- not now, stop thinking. The other is like watching an object pass by through a car window. With close enough attention, I started to feel this.

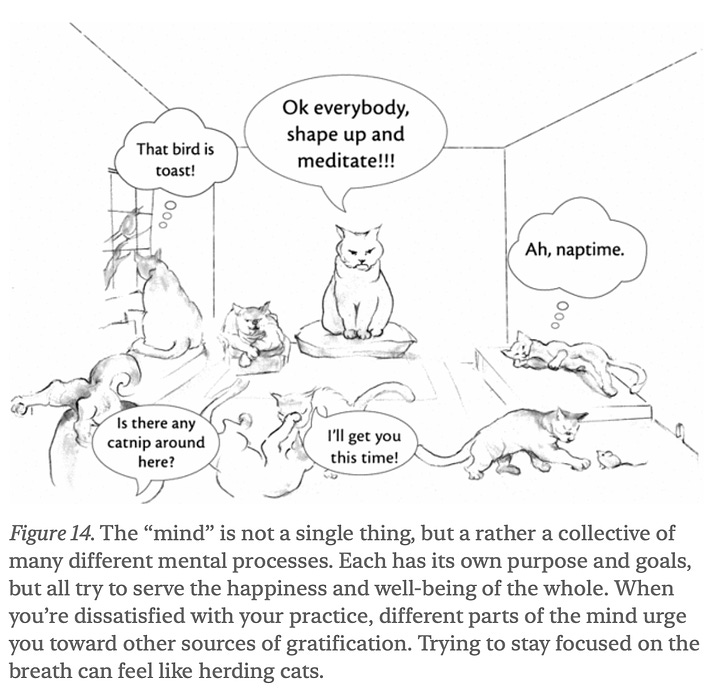

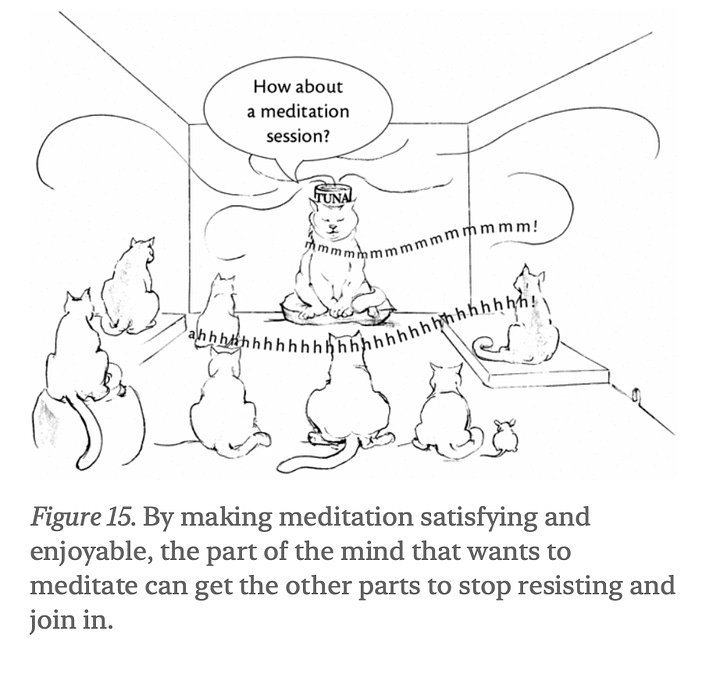

This is (I’m assuming) a novice meditation move, but here’s how I worked with that for the first few days. There’s an illustration from The Mind Illuminated that gets at this distinction.

Every time a thought arose, I greeted it, and asked it to line up with the other cats. I literally conceptualized each of my thoughts as cats. When does this work? A cat. My hips are tight. Cat. Why does Andrew Huberman annoy me so much?6 Cat. This was like, cute and kinda dumb, enough that it stopped stressing me out about thinking so much. It worked. What began as a parade slowed to a few strays.

Pause just to emphasize: that’s the mental architecture I was working with before I hit jhana. No extraordinary focus. Relaxation and some cats.

Continue: On the afternoon on the second day — probably my tenth hour of practice — I switched from a long relaxation body scan to metta. I’d been hopping around in my object of attention: an old friend I haven’t seen for a decade, a wedding I’d just attended, some fleeting memories of summer camp. Then I switched to thinking of my partner and my dog, images of a day we spent laugh-crying in hysterics at Baker Beach. I took that feeling and I made that feeling my focus. I stayed with it for a few minutes.

Then a tingle, a buzz, a levity appeared at a point just above my eyes. My breathing became deeper and more rapid. I noticed the buzz, and as I did it did traced a circle around the crown of my head. I turned my attention towards it — I actually physically rolled my eyes up to meet it — and then I was lifted up into what felt like a wholly different plane. I felt a rush of euphoria centered around my skull, humming and electric, wash up and down my back.

Analogies that describe the jhanas are only slant rhymes. The experience for me was both like what I’d read about the first jhana but still qualitatively distinct. And the experience of each jhana is also different each time. If I had to describe this first experience it’s something like: edging is to orgasm as that shiver you get from ASMR is to the first jhana. Like, you know how the thing about ASMR (or those scalp massagers) is that it always feels like the experience wants to evolve into something more complete and all encompassing? First jhana feels like it’s something like that. But that only captures the physical pleasure. The emotional component is equally strong.

After that, my retreat shifted entirely. I could let myself relax what I realized I’d been carrying: an internal pressure to achieve. Liberated and lighter, I got excited that I had five more days to continue exploring. I hit J1 a second and third time.

I started to think of getting into jhana a little like the verse-jumping headsets in Everything, Everywhere, All At Once. Relax sufficiently enough, focus deeply enough, and the green light on the bluetooth headset turned on. (This analogy works on a couple of levels. There are also times when access into jhana feels like it’s flickering. Move towards it too early and you don’t get anywhere, and will need to re-center again. This is the yellow light that gets you into the universe with hot dog hands.)

I had a practice interview the morning of Day 3. The main instruction I got was to notice where I still held tension or resistance in the jhana, to relax it, and to refocus on the subtlety of the experience. With that instruction — I re-interpreted it similar to the canonical psychedelic guidance to let yourself float down the river — I found J2 and J3 in succession.

The third day was also when I had my first inclination that the practice was deeper than simply accessing nice feelings on tap. One of my sits in J3 ended imagining the deep contentment of lying with my daughter on my chest. But I’m not a parent yet. My partner and I have been debating when to have kids for years, finding lots of financial and logistical reasons to delay. But the resistance, if I’m being honest, is much stronger on my end. I am nervous about parenthood, about the change it brings, the usual stuff. While in jhana, my emotional resistance felt lessened, like something I could actually grapple with. The experience, in fact, if I was to pay attention to what I was feeling, seemed like something that might actually lead to deep contentment.

Jhanas one through three varied in degree and intensity and texture each time, but they were also analogous enough to experiences in my own life to feel familiar. I’ve had joy (J1), happiness (J2), and contentment (J3). The jhanas felt like those just of a different kind: distilled, essence of happiness, or pure, uninterrupted contentment.7

Then I sank down into fourth jhana. Everyone seems to have some kind of mind-blowing shout it from the rooftops moment in jhana. For most people that seems to happen in the first jhana. For me it’s the fourth. This is me shouting from the roof top:

The fourth jhana is to experience what noise-canceling headphones are to sound. It is climbing into bed on the first day of vacation after you’ve wrapped a months-long project. It is sitting down in the grass after finishing a marathon. It is the nothing that is not there and nothing that is. It’s the air conditioner in your brain shutting off — and you hadn’t realized it was on. It’s adderall in a float tank, a xanax in zero gravity. Take the equanimity and stillness you find in each of these, then put it through a sieve. It is looking up from your yoga mat at the trees and knowing: everything is fine, everything has always been fine, everything will always be fine.

It wasn’t the exact same feeling as that moment in the lawn. That experience still feels mystical to me. But it was similar enough that I got a flavor of the extent to which all of these experiences — mystical, psychedelic, jhanic — converge on a shared set of mental phenomenona. I think we’re in the very early days of elucidating this, and I think academia is actually going to get a lot more fun over the next decade, like the past two decades of psychology have basically been what behaviorism was to animal science.

Once I’d learned the fourth jhana, if I didn’t exert effort to stay with the first three, I would fall quickly into the fourth, like a magnet snapping to its pole. That’s remained true since I’ve been home, and it’s something I’m still trying to figure out.

Getting out: the formless jhanas

Jhanas five through eight, the “formless” jhanas, involve, uh, transcending material form and entering realms of infinite space (5), infinite consciousness (6), “no-thingness” (7), and neither perception nor non-perception (8).8 I only accessed the higher jhanas twice. I haven’t been able to access them since being home, so my familiarity with them is as theoretical as experiential. I’m not even going to name where I went in the text (supposition in footnote) because there appears to be a lot of discussion over to what extent people exaggerate their own “achievements” in jhana. For me the value I found speaks for itself.

You can either volitionally move through jhanas, or you can relax deeper and deeper into the experience and allow them to evolve. Different teachers give different instructions for deliberate passage. To move from the fourth to the fifth, for instance, you can contemplate space and notice that your perception has no edges, or alternatively to find a hole in what you see and expand it, or alternatively to extend compassion outward until it becomes literally boundless.

But none of these fully clicked for me while in jhana four (I think because there was too much effort involved on my my end.) So instead I simply hung out and practiced looking with ever more subtlety. I tried not to try.

By the fifth day, I’d stopped setting timers. I set an intention to spend as much time as I could between lunch and dinner in meditation. I ran through the first and fourth in about an hour, confident, now, that I could track the distinctive features of each. From four, I waited to see where to go next.

The formless jhanas have some of the ineffability of psychedelic experience, but where a trip can’t be put into words because of its dream logic phantasmagoria, for jhana it’s like trying to describe the shape of an object while blindfolded, and if you speak too loud it disappears . There are distinctive features everyone seems to agree on9, but most people who write about them devote a lot less wordspace relative to the first four.

So: I left the fourth jhana. But I did not get to any place that had hallmarks of the fifth. At some point, after seeming to float in still space for a while, the idea came to me unbidden that it was no longer necessary for me to be there. It was comical, actually, that I was there at all. Sometimes, on a trip, you’re given an option: to persist in your own ego or to let it dissolve. Not knowing what to do, I followed my own trip logic and gave up the idea of holding onto my consciousness. And I touched here the sense of a unitive consciousness — or even a mystical other — though only briefly. I felt freedom, a lifting, but incomplete, like an interrupted sneeze. What was left of I continued to observe.

Once, on five grams of psilocybin, I experienced the dissolution of everything. Kaleidoscopic colors that had comprised my trip faded first to black. The sound in my headphones disappeared entirely. The black then turned to white. My sense of my body disappeared entirely. Then even the white was gone, until whatever was left of me arrived at a place absent of color, physicality, and self. There were no things anywhere at all.

During this sit, I spent some time in a place extremely similar to this.10 The seventh jhana is known as “the realm of nothingness” or (better) “no-thingness.” I don’t know if this was that. It felt like I dreamed in and of a place with no-things.11

Still the experience evolved. I don’t really know what to say about what happened next. Images I can’t remember appeared in my consciousness. It felt like I was lucid dreaming from inside Plato’s cave. That’s all I’ve got.

And then I found myself, without trying to go there, back in J4. I became conscious, suddenly, of not knowing where to go. I could have opened my eyes. Instead, still feeling focused, I stayed.

I knew for sure that I hadn’t experienced the fifth jhana, and decided to try and go there again. One of the instructions we worked with for fifth jhana was to expand compassion outward. Resolved to that, I realized I didn’t really know what the difference between metta and compassion was supposed to be. I didn’t know who to feel compassion for. I reached, and my school photo from first grade is what I caught.

I had (maybe we all had) an emotionally turbulent childhood. From this place of deep equanimity, I suddenly felt this intensely. Remembered, somatically, the experience of being a kid, and yet experienced it as my adult self, which grieved over years of emotional dysregulation. But that feeling was simultaneously matched by — or maybe even better, contained within — an overwhelming sense of gratitude: for the way my life has unfolded, for the things I’ve been able to, for the person I became. I cried, lightly, feeling both sorrow and pride. And then I heaved for a minute through some autonomic belly sobs.

I opened my eyes. I laid there staring at the ceiling for a few minutes. And then — let me stress how unusual this is, but it felt like the exact right thing to do at the time — I put on a song and danced.12

When I looked at the clock, three and a half hours had passed.

—

Jhanas are sometimes discussed as peak experiences. That never made sense to me. Daily jhana practice can’t, by definition, stand out. But that sit did. I felt all the catharsis of a trip without having to first take a ride on Willy Wonka’s wondrous boat ride to get to the inventing room. Jhana practice felt in comparison like a lazy river.

By the end of the retreat, my time to access jhana had dropped to minutes. And — coming back to Everything, Everywhere — I realized that I didn’t need a headset or green light to get there. I could access the first four jhanas while walking. I would stare up at the sky, conjure some joy, kick myself into first, then come down into the fourth. The experience was lighter, like holding holding a stretch for seconds instead of minutes, and I could keep it only a quarter mile or so at a time. On the last morning, I ran with headphones for the first time. Music had taken on new resonance. Emotions were coming through with greater clarity. Some songs were moving me in between jhanas as I ran.

What do I do with all this joy I’m getting?

There were some immediate tangible benefits. My first week home absolutely sparkled. I’m more social. My smile is always under the surface, not something I need to work towards. I went from 3-4 drinks a week to none. I’m waking up around 5:30 every day without an alarm, and though I’m sleeping less, my HRV has gone up.

I’d find my attention snapping away from my screen to birdsong, or just the simple sensations of my body moving through space. For a day or two I thought I’d tuned into the vibration of the universe. Then I realized: I have tinnitus.

It’s been a few weeks now, and that experience has leveled out. But my baseline happiness and delight seems to have stabilized quite a few notches above where I began. Maybe more noticeable is that the low-running existential dread I seemed to be always carrying in the background has mostly faded away. Are EA-ish engineers attracted to jhanas because of the way their brain works, or because they’re all desperate to ease the angst of AGI?

Why did I have a relatively easy time accessing jhana, despite having no meditation practice to speak of? I can point to a few things. Brasington, a self-described former pothead who still seems to come alive when hallucinogens are mentioned in his vicinity, has said he can tell someone’s previous drug use by their ease accessing jhana.

I also think that my yoga practice carried over. And I think that Nadia broke for the four-minute mile. I spent many hours with her piece, and maybe more importantly, saw her change in understanding, that I had a good sense of what was on tap. And like Nadia, my day-to-day happiness was already quite high. I think a lot of this may also just be genetic. Give it a few years and we’ll know more.

My hunch is that jhanas are about to explode into mainstream. Oshan’s article gestures at that (while also facilitating it). More pieces are coming. Nadia’s primer appears to have gotten several people into jhana (possibly formless jhanas) within hours. Jhourney has been scaling access faster than probably all teachers in the past.

But now we’re starting to enter territory where jhanas are going to spread through network effects. Does that come with risks, compunctions with respect to tradition, possible misunderstandings etc. etc.? Yes, of course, and we should be cognizant of ways to scale support. But we should also be excited about the potential.

A year and a half ago, one of the talking point about jhana was whether they were addictive. From the other side, this now seems comical, a little like the way D.A.R.E programs liked to talk about cannabis as the gateway drug to heroin. On their website, Jhourney still describes jhanas as “non-addictive.” Nick and Stephen use a water analogy: even if you begin ravenously thirsty, you no longer crave water after you’ve had your fill. That’s a fine way to think about it, but I think you can push it further. Jhanas are how you realize that you’ve been standing knee-deep in water the whole time.

This is how growing up, evolving, learning, always seem to feel, at least to me. I’ve spent so much time — through therapy and self-enquiry and whatever form of analytical thought — looking for answers to questions that plague me, but when I look back at my own growth, it was never inspired by finding an answer or identifying some Freudian root. I just learned, through whatever grace, to drop the question.

Jhanas are one way to drop the questions. I don’t think that it’s a coincidence that my experience on the lawn happened after I’d been trying to intellectually understand mysticism. I had to let analysis go before feeling could arise. Jhanas feel like a way to fast track this understanding. That underneath the thinking brain, I have everything I already need.

It was strange at first to have picked up an “advanced meditative skill” without having any meditation practice. It felt a little like I learned to make hollandaise sauce without having any idea how to poach an egg — or for that matter, to toast bread. But the answer was obviously not keep spoon-feeding myself the hollandaise. It seems obvious that if I missed jhana, I missed a lot of other stuff along the path.

So I’ve been exploring other techniques. I recently switched from metta to breath meditation and found my way into the jhanas from there. I’ve been using jhana practice as a jumping off point for non-dual practice. And most of my free time has been spent learning: more about jhana, but also other traditions. The important thing here is that I doubt I would have ever gotten interested in the path except through a Jhourney retreat. I went from not meditating at all to practicing consistently for at least an hour a day.

Independent of the jhanas, what I learned on retreat was deeply rewarding. Metta (and forgiveness meditations) impacted my affect first subtly, and then all at once. But jhanas were undoubtedly an accelerant to insight into my conscious experience. It’s not that I learned a new way to slake my thirst. Jhanas aren’t actually the water. The water’s been there the whole time.

The core elements of mystical experience are a sense of oneness, insight into ultimate reality, or sacredness, a transcendence of time and space, ineffability, and positive mood. There’s a newer scale that came out this March that filters the 30 question scale used in most trials into just 4. I also like Katherine MacLean’s line from my piece: ““It’s mostly this one big factor. Did you experience God?”

I also think parts of it are interpretable as a non-dual experience, but I didn’t really learn about those until two weeks ago, so I’m going to stick to jhanas here.

Including Focused and Fearless by Shaila Catherine and Practicing the Jhanas by Stephen Snyder and Tina Rasmussen, in addition to Brasington’s book above.

FYI, Jhourney uses “friendliness.” I’m using metta.

Long footnote here. Jhanas can be access through a lot of different techniques. The Tranquil Wisdom Insight Meditation (TWIM) community teaches them through metta. Jhourney draws most closely on this for their instructions. Leigh Brasington, Shaila Catherine, and other teach it primarily through a focus on the breath. Rob Burbea, whose jhana retreat recordings are popular on YouTube, encourages both but also teaches emphasis on (if I’m getting this right) the energy body, or an integrated sense of the body in space, including its vibrations and feelings, beyond pure physical sensation.

There is a longstanding debate over to what extent you need to be concentrated and absorbed for a jhana to count as a jhana. Pa-Auk Sayadaw, among others, teach a deeper form in which background thoughts drop to almost zero for several hours. What Jhourney, TWIM, and Brasington teach are sometimes therefore called “light jhanas.” Lots of people have lots of thoughts about this and all of the above. Don’t at me, I know nothing, not meditation advice.

Like a stray I’d fed out of sympathy, this one weirdly kept returning.

I’m skipping a lot here for space. If you want more on 2 and 3, I recommend, and will keep recommending, Rob Burbea.

You may be tempted to get off the crazy train here. But I don’t know. Imagine being ignorant of the Grand Canyon, or of orgasm, and hearing someone explain it for the first time. But if that still doesn’t work, it’s no problem. I was not open to this until I experienced it.

To what extent jhanic experience is informed by expectation seems like an open question, and I haven’t seen anyone talk about it much. Psychedelics are culturally influenced by a meta-level set and setting. I’m not sure whether the same is true of jhanas, and that would be a hard experiment to run.

Interestingly enough, a lot of my own psychedelic experience matches up better with the formless jhanas than it does how I often hear people talk about psychedelic experience.

My interpretation after talking to a few facilitators is that I skipped J5 and spent some time in J6 and J7, but please put low credence on this.

Loved reading this Jake, and loved having you on retreat. You capture here so much that’s hard to put into words about the jhanas: their ineffable and laughably nonaddictive nature, and most importantly, how they can catalyze meaningful personal change. Here’s to tools that make it easier to be people we already aspire to be.

Such a great read. Thanks for so clearly sharing your experience, and perhaps one of the simplest encapsulations of Jhourney's instructions!